In this article we will illustrate the most common German prepositions of time and place

German prepositions can be quite confusing when one first approaches them. Practice usually helps grasping the differences among them but, for the moment, we will try to explain this topic as easy as possible, so that you can immediately start learning.

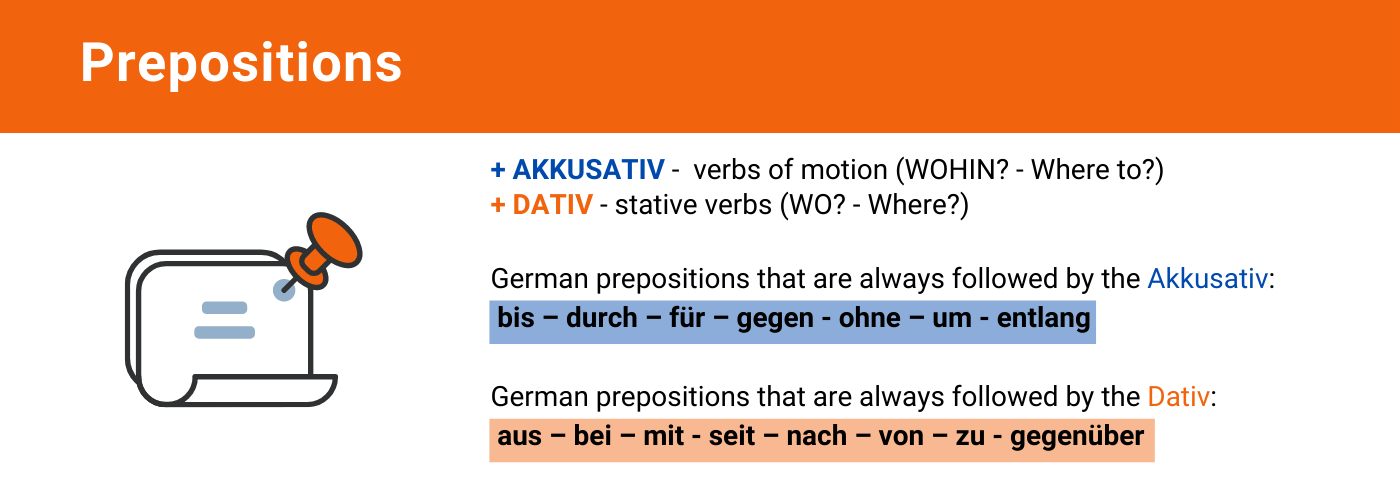

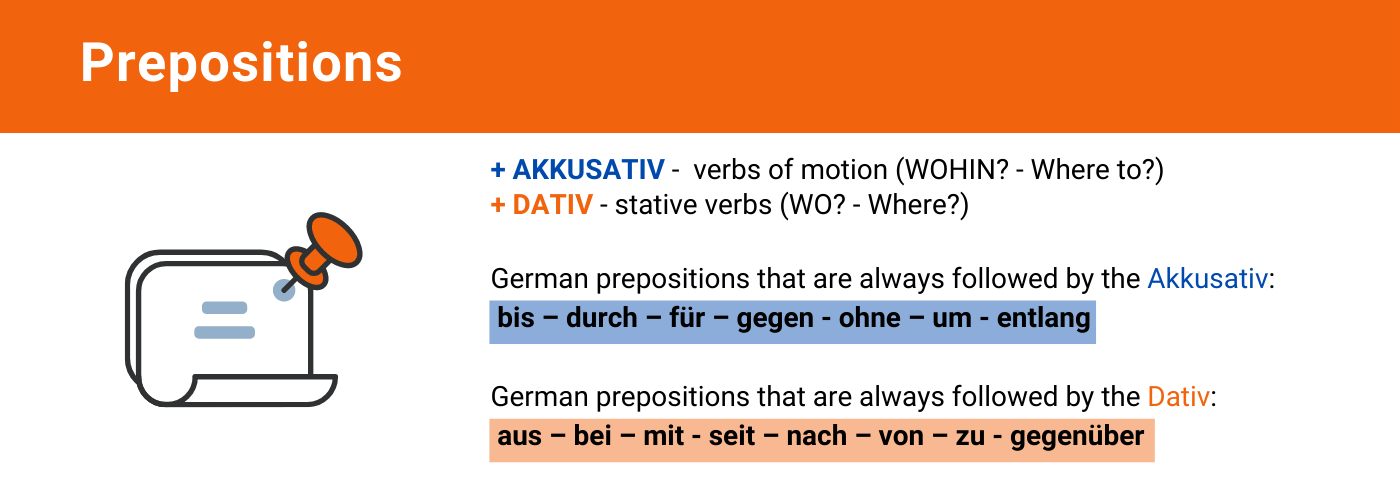

Some German prepositions are always followed by the Akkusativ. These are: bis – durch – für – gegen – ohne – um – entlang.

Other prepositions are always followed by the Dativ: aus – bei – mit – seit – nach – von – zu – gegenüber.

There are also prepositions that can either be followed by the Akkusativ or by the Dativ. These are usually prepositions of place, and they follow this general rule:

Prepositions of time

AN + Dat. It is used with the days of the week (am Montag) and the parts of the day (am Vormittag), except for the night (in der Nacht).

IN + Dat. It is used with months (im Juli), seasons (im Sommer) and years (in 2021, im Jahr 2021). “In” can also be used to say “in a week”, “in a month” and so on: in einer Woche, in einem Monat.

INNERHALB + Gen. (within). E.g.: Ich schreibe dir innerhalb einer Woche. – I’ll write to you within a week.

ZU is used with feast days (zu Ostern, zu Weihnachten) and expressions like “zu dieser Zeit” and “zu jeder Zeit”.

FÜR + Akk. (for) indicates the duration: Für eine Stunde, für einen Monat, für drei Tage…

VON + Dat … BIS + Akk. (from…to). E.g.: Von Montag bis Freitag. – From Monday to Friday.

“Bis” can also be employed in expressions like: Bis bald! / Bis Montag! – See you soon! / See you on Monday!

ZWISCHEN + Dat. (between). E.g.: Zwischen dem 1. Januar und dem 1. Februar. – Between the 1st of January and the 1st of February.

WÄHREND + Gen (during). E.g.: Während dem Sommer habe ich viele Bücher gelesen. – During the summer I read a lot of books.

Um vs. Gegen

UM + Akk. (at). It is used to indicate what time it is. E.g.: Wir treffen uns um 19 Uhr. – We are meeting at 19.

GEGEN + Akk. (around). E.g.: Wir beginnen gegen 10 Uhr. – We begin around 10.

Vor and Nach

VOR + Dat. (before). E.g.: Vor dem Deutschkurs habe ich Zeit zum Essen. – I have time to eat before the German course.

NACH + Dat (after). E.g.: Ich komme nach der Schule. – I’m coming after school.

Vor, Seit and Ab

VOR also means “ago” (always with Dativ). E.g.: Vor einer Woche hatte ich Fieber. – A week ago I had a temperature.

SEIT + Dat. (since/for). “Seit” is used to talk about an action that started in the past and that is not yet completed. E.g.: Ich lerne Spanisch seit zwei Monate. – I’ve been learning Spanish for two months.

Ich lerne Spanisch seit Januar – I’ve been learning Spanish since January.

AB + Dat. (from). It can also be used with the Akkusativ if it comes with no article. E.g.: Ab dem nächsten Monat/ ab nächsten Monat.

“Ab” is usually used for the future. We can’t say “Ich warte hier ab 15 Uhr” if it is 16.

It can also be employed to refer to the past, but only if the action is completed.

E.g.: Ab 1952 arbeitete er in Berlin. – From 1952 he worked in Berlin (but now he doesn’t).

Prepositions of place

The meaning

IN (inside)

VOR (in front of)

HINTER (behind)

UNTER (under)

ÜBER (on – without contact)

AUF (on – with contact)

NEBEN (close to – without contact)

AN (next to – with contact)

ZWISCHEN (between)

All of these prepositions are used with the Dativ if they give a location (WO?), and with the Akkusativ if they give a direction (WOHIN?).

Dativ vs Akkusativ

As we said before, prepositions of place often depend on whether there is a motion or not. We have to ask ourselves if the sentence answers the question WO? (where?) or WOHIN? (where to?).

IN + AKK Ich gehe in die Stadt. gehen = verb of motion, WOHIN?

IN + DAT Ich bin in der Stadt. sein = stative verb, WO?

Prepositions of place that are always used with the accusative case.

DURCH + Akk. (through). E.g.: Sie wandern durch den Wald. – They’re walking through the woods.

ENTLANG + Akk. (along). E.g.: Wir spazieren diese Straße entlang. – We’re walking along this street.

UM + Akk. (around).

Wir sitzen um den Tisch. – We’re sitting around the table.

Das Restaurant ist um die Ecke. – The restaurant is around the corner.

GEGEN + Akk. (against). E.g.: Gegen die Mauer. – Against the wall.

Prepositions of place that are always used with the dative case.

AUS + Dat. (from). E.g.: Ich komme aus Italien. – I come from Italy.

ZU + Dat. (to). We find it in front of persons or professions to indicate a direction.

Ich gehe zu meiner Mutter. – I’m going to my mom’s house.

Er geht zu Lisa. – He’s going to Lisa’s house.

Ich gehe zum Arzt. – I’m going to the doctor’s.

If there is no motion involved (WO?) we use BEI (+ Dativ).

Ich bin bei meiner Mutter. – I’m at my mom’s house.

Er ist bei Lisa. – He is at Lisa’s house.

Ich bin beim Arzt. – I’m at the doctor’s.

ZU is also used with “Haus(e)”. In this case, though, it gives a location, and not a direction: Ich bin zu Hause. – I’m at home.

If we want to say “I’m going home”, we employ NACH instead: Ich gehe nach Hause.

NACH also belongs to the prepositions used with the Dativ. It always refers to a direction (WOHIN?). We employ it with those geographical names that come with no article (cities and towns, most countries, continents).

Ich fahre nach Berlin. – I’m going to Berlin.

Wir fahren nach Spanien. – We’re going to Spain.

Sie fliegen nach Asien. – They’re flying to Asia.

In these same cases, we use IN to give a location.

Ich bin in Rom. – I’m in Rome.

Wir sind in Frankreich. – We’re in France.

Sie sind in Europa. – They’re in Europe.

Prepositions of place that can either be used with the dative or with the accusative case.

Geographical names with article

IN + Akk. gives a direction.

Ich fahre in die Schweiz. – I’m going to Switzerland.

Wir fliegen in die USA. – We’re flying to the USA.

Ich fahre ins Ausland. – I’m going abroad.

IN + Dat. gives a location.

Ich bin in der Schweiz. – I’m in Switzerland.

Wir sind in den USA. – We’re in the USA.

Ich bin im Ausland. – I’m abroad.

Islands and open spaces

AUF + Akk. is used to give a direction.

Ich fliege auf die Insel Sylt. – I’m flying to Sylt island.

Wir gehen auf den Markt. – We’re going to the market.

AUF + Akk. is used to give a location.

Ich bin auf der Insel Sylt. – I’m on Sylt island.

Wir sind auf dem Markt. – We’re at the market.

Seas, oceans, lakes, rivers and beaches

AN + Akk. gives a direction. E.g. Ich gehe ans Meer. – I’m going to the seaside.

AN + Dat. gives a location. E.g. Ich habe ein Haus am Meer. – I have a house by the sea.

Let’s practice

Wohin möchtest du fahren/gehen? – Where would you like to go?

Make a list of the places you would like to visit, using the prepositions seen above.

E.g.: Ich möchte nach Paris fahren.

Learning German with Berlino Schule

Berlino Schule offers German courses from A1 to C1. Our school has the best quality-price ratio (check the reviews online, 4.9/5 on Google and Facebook). Click here to access the calendar and reserve your place by simply sending an email to info@berlinoschule.com.

Our contacts

Gryphiusstraße 23, 10245 Berlin-Friedrichshain

+49 030 36465765

info@berlinoschule.com

Facebook page

Instagram profile

Tedesco Goethe German language studiare tedesco

Tedesco Goethe German language studiare tedesco